By Georgia Jackson, University Communications and Marketing

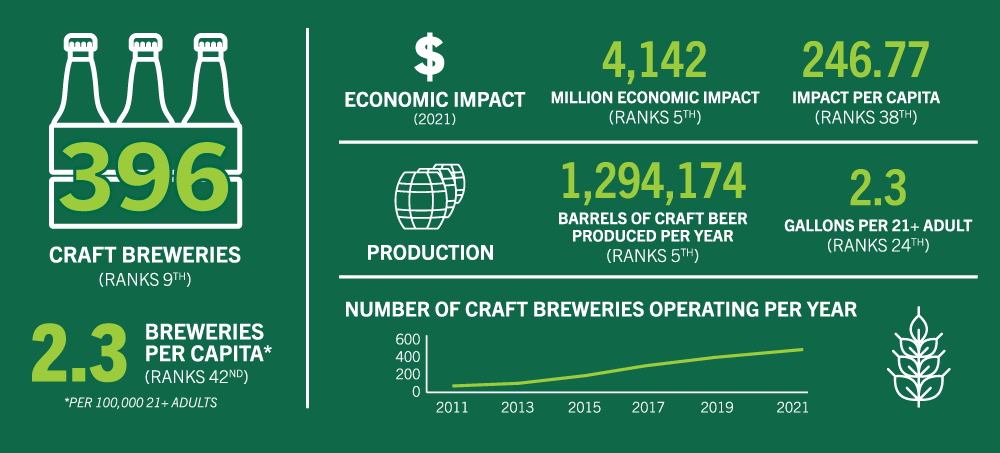

The Florida craft brewing industry generates a ton of waste each year. For every barrel of beer brewed, about 50 pounds of spent grain and residual yeast remain. Multiply that by Florida’s annual production of 1.2 million barrels of craft beer and you end up with an annual sum of 33,480 tons of waste.

Much of the spent grain is given to local farmers, who use it to feed livestock. The rest — the yeast and hops — is discharged to the nearest treatment plant, which comes at a cost to everyone involved. Not only do wastewater and sewage treatment plants emit greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide — all of which contribute to global climate change — but because high-strength wastes, like spent grain and residual yeast, require more energy to treat, some municipalities levy a surcharge.

An internal grant — and the prospect of developing new and sustainable solutions that account for the tons of waste produced by the craft brewing industry — brought Sarina Ergas and Qiong Zhang, both professors in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering; Paul Kirchman, dean of the College of Arts and Sciences on the Sarasota-Manatee campus; and three USF students, Dhanashree Rawalgaonkar, Yan Zhang and Selina Walker, together to consider how byproducts of the brewing process might be reused to minimize waste and improve efficiency.

“It takes a lot of energy to run a brewery,” said Kirchman, who also teaches biology courses on the Sarasota-Manatee campus. “They have to boil these large volumes of liquid. And if you can get some methane out of the waste and use that to boil beer ... you could save money in a couple different ways.”

Can residual yeast be transformed into methane gas?

Ergas, Zhang, Kirchman and their students set out to discover whether the residual yeast produced by craft breweries could be turned into methane gas through anaerobic digestion and used as an energy source — and whether the practice would be economically feasible for local craft breweries, like Motorworks Brewing and Calusa Brewing, both of which donated brewer’s waste for the study.

“Anaerobic digestion is a common practice for large breweries, but craft breweries produce a lot of hoppy beers like IPAs, and the compounds in hops that give beer its bitter taste can inhibit anaerobic microbes,” Ergas said. “We wanted to find out whether these compounds would significantly inhibit methane production in anaerobic digesters.”

The team also looked at the possibility of recovering carbon dioxide from the brewing process to use in carbonating the beer.

“The irony is the yeast make all this carbon dioxide during fermentation, and the breweries buy these tanks of carbon dioxide to put back in the beer to carbonate it,” said Kirchman. “But they’re blowing all this carbon dioxide off as they’re doing this.”

To put their theory to the test, the group created a mixture of yeast and anaerobic microbes — also known as sewage sludge. Then they waited patiently for the chemicals to react.

“Normally, if bacteria eat dead stuff, they produce carbon dioxide, but if you take away all the oxygen, they have to make methane. And you can burn methane, it’s a fuel source,” Kirchman said.

The whole thing was, admittedly, “kind of gross,” but the team was able to conclude that the hops did not significantly affect the process, and that the practice might be economically feasible for intermediate sized breweries.

What about spent grain?

The team hoped to prove the spent grain, like the residual yeast, could be transformed into methane gas and used as an energy source. However, while the team did manage to achieve a decent production of methane from the grain, Kirchman said the effort wasn’t, ultimately, worth it.

“We mixed this sewage sludge with this grain, but the bulk was not reduced much and, in the end, what you ended up with was a whole lot of grain waste covered in sewage sludge and a bigger mess than what you started with,” said Kirchman, whose primary research focuses on yeast and aging. “There’s a lot of stuff in the grain that’s just not digestible in any reasonable period of time, so the volume wasn’t really decreased. So, you had 20 pounds of spent grain and you end up with 20 pounds of stuff covered in sewage sludge.”

In the end, the team concluded brewers should continue to make their waste available for pick up by local farmers.

Despite the final result, Walker, who is majoring in microbiology, called the experience “enriching,” and said it inspired her to pursue research as a career and to, one day, become a professor, herself.

“Working with Dr. Kirchman and Dr. Ergas exposed me to wet lab research and provided me the opportunity to present at various conferences,” she said.

Rawalgaonkar, a graduate student in the College of Engineering who presented the team’s findings at the 2023 Student Research Showcase, shared similar sentiments and said the project helped her better understand the local waste management systems and the role engineers play in safeguarding them.

“It’s not the worst thing to have an idea and find out it’s a bad idea, because then you know it was a bad idea,” said Kirchman, who expressed interest in continued collaborations with breweries and suggested he might be interested in developing new strains of yeast for use in the brewing process.